The US Constitution of 1787

Created September 17, 1787

Ratified June 21, 1788

Implemented March 4, 1789

The United States Constitution of 1787

A Brief History

In 1787 Philadelphia a reasonable quorum of States assembled in

convention to “revise” the Articles of Confederation. James Madison reports:

Friday 25 of May … Mr Robert Morris informed the members assembled that by the

instruction & in behalf, of the deputation of Pena. he proposed George

Washington Esqr. late Commander in chief for president of

the Convention. Mr. Jno. Rutlidge seconded the motion; expressing his

confidence that the choice would be unanimous, and observing that the presence

of Genl Washington forbade any observations on the occasion which might

otherwise be proper.

General (Washington) was accordingly

unanimously elected by ballot, and conducted to the chair by Mr. R. Morris and

Mr. Rutlidge; from which in a very emphatic manner he thanked the Convention

for the honor they had conferred on him, reminded them of the novelty of the

scene of business in which he was to act, lamented his want of (better

qualifications), and claimed the indulgence of the House towards the

involuntary errors which his inexperience might occasion.

The “more or less” United

States’ Assembly was attended by 12 States[1]

whose delegates elected George Washington as the Philadelphia Convention’s

president. Washington began the first session by adopting

rules of order which included the provision of secrecy. No paper could be removed from the Convention

without the majority leave of the members.

The yeas and nays of the members were not recorded and it was the

unwritten understanding that no disclosure of the proceedings would be made

during the lives of its delegates. At

the end of the convention Washington ordered that every record be burned except

the Journals which were merely minutes, of which he took personal

possession. “We the People” of the United States,

therefore, knew very little about the Convention until the Journals were

finally published in 1819. It was not

until the death of President James Madison that his wife, Dolley, revealed she possessed

his account of the convention. Dolley

Madison sold these journals to the Library of Congress in 1843.

|

| US Constitution Day at Loyola University New Orleans September 17, 2014 |

The delegates of the

convention were given no authority by the USCA to scrap the Articles of

Confederation and construct a new constitution in its

place. Throughout the proceedings this

fact was addressed in debate and federally-minded delegates led by George

Washington, James Madison, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton and Charles Pinckney all stood firm on formulating an entirely new

constitution. The larger states (by population), especially, were determined to

change the one state one vote system adopted under the Articles of

Confederation to enact legislation and construct a strong central governmental

authority. The smaller states sought to

preserve independent state sovereignty and the USCA system of casting votes

equally. The two sides, as they did in the York Courthouse[2] formulating the Articles of Confederation in

1777, clashed once again on issue of States rights over federalism.

Edmund Randolph submitted the large states’ “Virginia Plan” that was primarily drafted

by James Madison. There were other

plans, most just seeking revisions to the Articles of Confederation.

Surprisingly, the 29 year old delegate from South Carolina, Charles Pinckney, provided a plan of

a federal structure and powers that was more tangible than any other plan. Pinckney's plan was actually a nascent form

of the constitution that would be eventually be passed by the Philadelphia convention of States.

The small states formed a

sub-committee in an attempt to develop an alternate plan for a newly-proposed bicameral

legislature only to emerge still insistent that the one-state one-vote unicameral

USCA be retained. The “New Jersey Plan”[3] proposed

improvements called for a weak federal executive and judiciary branches. The

federal government was to remain a confederation with the requirement of at least nine states

voting in the positive to enforce their decrees. Although there were many challenges, none was

more crucial than the acceptance of a bicameral legislature and how the

representatives and senators would be finally numbered in the two newly

proposed congressional bodies. The impasse loomed over the proceeding with the large

States insisting that all members, in both the House and Senate, be selected

based on population. The small States disagreed, but with Rhode Island absent, they

lost the convention vote 7-5 on this matter to the large State voting bloc.

State

|

1776 US Population*

|

1790 US Census

|

Virginia

|

540,000

|

747,610

|

Pennsylvania

|

310,000

|

434,373

|

North Carolina

|

280,000

|

393,751

|

Massachusetts

|

270,000

|

378,787

|

New York

|

240,000

|

340,120

|

Maryland

|

230,000

|

319,728

|

South Carolina

|

180,000

|

249,073

|

Connecticut

|

170,000

|

237,946

|

New Jersey

|

130,000

|

184,139

|

New Hampshire

|

105,000

|

141,885

|

Georgia

|

60,000

|

82,548

|

Rhode Island

|

50,000

|

68,825

|

Delaware

|

45,000

|

59,096

|

United States

|

2,610,000

|

3,637,881

|

* Author Estimates

|

Mr. L. MARTIN resumed his discourse, contending that the

Genl. Govt. ought to be formed for the States, not for individuals: that if the

States were to have votes in proportion to their numbers of people, it would be

the same thing whether their representatives were chosen by the Legislatures or

the people; the smaller States would be equally enslaved; that if the large

States have the same interest with the smaller as was urged, there could be no

danger in giving them an equal vote; they would not injure themselves, and they

could not injure the large ones on that supposition without injuring themselves

and if the interests, were not the same, the inequality of suffrage wd. be

dangerous to the smaller States: that it will be in vain to propose any plan offensive

to the rulers of the States, whose influence over the people will certainly

prevent their adopting it: that the large States were weak at present in

proportion to their extent: & could only be made formidable to the small

ones, by the weight of their votes; that in case a dissolution of the Union

should take place, the small States would have nothing to fear from their

power; that if in such a case the three great States should league themselves

together, the other ten could do so too: & that he had rather see partial

confederacies take place, than the plan on the table. This was the substance of

the residue of his discourse which was delivered with much diffuseness &

considerable vehemence.[4]

On June 28, 1787 the small

States gave an ultimatum to the convention that, unless representation in both

branches of the proposed legislature was on the basis of equality, one-state

one-vote, they would forthwith leave the proceedings. With tempers flaring, Benjamin Franklin rose and called for a recess with the

understanding that the delegates should confer with those with whom they

disagreed rather than with those with whom they agreed. This recess resulted in a crucial compromise

of the convention: The House of

Representatives was to be elected by the people based on population, thus

providing more representation in the new federal government to the large

states. This House, however, was to be

checked by the Senate where each state, regardless of size, would have two votes. This resolution to the great Philadelphia Convention

crisis enabled the delegates to labor another two months to create one of the

most elastic forms of government in human history. And the convention’s new plan for the federal

government that scrapped the Articles of Confederation consisted of less than four thousand words.

The innovative Plan of the New Federal Government was

passed on September 17th, 1787, and rushed to New York by stagecoach.

The new constitution was presented to Congress along with a letter from

the convention’s President, George Washington, to USCA President Arthur St. Clair:

Plan of The New Federal Government,

Printed by Robert Smith, September 1787

Image Courtesy of Stan Klos Collection.

SIR, -- WE have now the honor to submit to the consideration of the United States in Congress assembled,

that Constitution which has appeared to us the most adviseable. The friends of

our country have long seen and desired, that the power of making war, peace and

treaties, that of levying money and regulating commerce, and the correspondent

executive and judicial authorities should be fully and effectually vested in

the general government of the Union: but the impropriety of delegating such

extensive trust to one body of men is evident—Hence results the necessity of a

different organization. It is obviously impracticable in the federal government

of these States, to secure all rights of independent sovereignty to each, and

yet provide for the interest and safety of all—Individuals entering into

society, must give up a share of liberty to preserve the rest. The magnitude of

the sacrifice must depend as well on situation and circumstance, as on the

object to be obtained. It is at all times difficult to draw with precision the

line between those rights which must be surrendered, and those which may be

reserved; and on the present occasion this difficulty was encreased by a

difference among the several States as to their situation, extent, habits, and

particular interests.

In all our deliberations on this subject

we kept steadily in our view, that which appears to us the greatest interest of

every true American, the consolidation of our Union, in which is involved our

prosperity, felicity, safety, perhaps our national existence. This important

consideration, seriously and deeply impressed on our minds, led each State in

the Convention to be less rigid on points of inferior magnitude, than might

have been otherwise expected; and thus the Constitution, which we now present,

is the result of a spirit of amity, and of that mutual deference and concession

which the peculiarity of our political situation rendered indispensible. That

it will meet the full and entire approbation of every State is not perhaps to

be expected; but each will doubtless consider, that had her interests been

alone consulted, the consequences might have been particularly disagreeable or

injurious to others; that it is liable to as few exceptions as could reasonably

have been expected, we hope and believe; that it may promote the lasting

welfare of that country so dear to us all, and secure her freedom and

happiness, is our most ardent wish. With

great respect, we have the honor to be, SIR, Your EXCELLENCY'S most obedient

and humble Servants,

George Washington, President.

By unanimous Order of the

CONVENTION.

HIS EXCELLENCY

The President of Congress [5]

The Convention delegates

called for the Plan of The New Federal

Government to be sent to the states for their consideration with only

2/3rds of their legislatures being required to discard the Articles of

Confederation for the new constitution. The convention overstepped the authority

granted by the seventh USCA on February 21st, 1787, by first

discarding the Articles instead of revising that constitution and second, by completely

dismissing the modification requirements set forth in Article XIII of the

federal constitution that stated:

Every State shall abide by the

determination of the United States in Congress assembled, on all questions

which by this confederation are submitted to them. And the Articles of

this Confederation shall be inviolably observed by every State, and the Union

shall be perpetual; nor shall any alteration at any time hereafter be made in

any of them; unless such alteration be agreed to in a Congress of the United

States, and be afterwards confirmed by the legislatures of every State.[6]

The proposed obliteration of

the Articles of Confederation by

convention was to be accomplished without the unanimous approval by the States.

It was a constitutional crisis that, to this day, has not been equaled in the

United States save by the southern secession of the 1860’s forming the

Confederate States of America.[7]

Only sketches of the great

debate that ensued in the 1787 USCA exist due to the veil of secrecy that

surrounded the sessions. We do know from the notes of New York delegate Melancton Smith, which became available

to the public in 1959, that most USCA Delegates believed they had the authority

to alter the new proposed Constitution of 1787 before it was sent on to the

States. James Madison, Rufus King, and Nathaniel

Gorham argued, however, to the contrary.

Since there was no Supreme

Court, the USCA was the final authority on the new

constitution judicially as well as legislatively. Virginia Delegate Richard Henry Lee would lead the “9-13 opposition” that insisted

on unanimous State convention ratification.

Lee also sought to amend the new constitution. Melancton Smith writes of

Lee:

RH LEE -- The convention had not

proceeded as this house were bound; it is to be agreed to by the States &

means the 13; but this recommends a new

Confederation of nine; the Convention has no more powers than Congress, yet if

nine States agree becomes supreme Law. Knows no instance on the Journals as he

remembers, opposing the Confederation the impost was to be adopted by 13.

This is to be adopted & no other

with alteration Why so? good things in it; but many bad; so much so that he

says here as he will say everywhere that if adopted civil Liberty will be in

eminent danger.[8]

Despite

such arguments, Rufus King, James Madison, and Nathaniel

Gorham – all delegates

to both the Philadelphia Convention and the USCA – maintained that Congress must

keep the new constitution intact, sending it on to the States without any

changes or amendments despite the unanimous requirement in Article XIII. Smith records Richard Henry Lee’s reaction to

their position:

Strangest doctrine he ever heard, that

referring a matter of report, that no alterations should be made. The Idea the

common sense of Man. The States & Congress he thinks had the Idea that

congress was to amend if they thought proper. He wishes to give it a candid

enquiry, and proposes such alterations as are necessary; if the General wishes

it should go forth with the amendment.; let it go with all its imperfections on

its head & the amendments by themselves; to insist that it should go as it is without amendments, is like

presenting a hungry man 50 dishes and insisting he should eat all or none.[9]

Virginia delegate James Madison’s response was:

The proper question is whether any

amendments shall be made and that the house should decide; suppose altercations

sent to the State, the Acts require the Delegates to the Constitutional

Convention to report to them; there will be two plans;

some will accept one & some another this will create confusion and proves

it was not the intent of the States.[10]

Massachusetts

Delegate Nathaniel Gorham, who served as Deputy Chairman of the

Philadelphia convention, is reported to have argued against

USCA amendments to the new constitution:

Gorham thinks not necessary to take up

by paragraphs, every Gentn. may propose amendments; no necessity of a Bill of

rights; because a Bill of Rights in state Govts. was intended to retain certain

powers, as the [state] legislatures had unlimited powers.[11]

Gorham, although

correct in his counsel for the USCA not to amend the constitution, was wrong in

his assertion that States’ retained enforcement of their “unlimited powers.” Even the 10th Amendment to the U.S.

Constitution enacted passed in the 1790’s failed in preserving the “unlimited powers” of the

Articles of Confederation state legislatures.

In addition to the

discussions of whether or not the USCA should alter or amend the Constitution, the question:

“If not altered how should it be

submitted to the States?” was also debated. Smith reports on New Jersey Delegate Abraham

Clark:

Clark don’t like any proposal yet made;

he cant approve it; but thinks it will answer no purpose to alter it; will not

oppose it in any place; prefers a resolution to postpone to take up one, barely

to forward a copy to the States, to be laid before the Legislatures to be

referred to conventions.[12]

It was reported of Virginia Delegate

William Grayson:

This is in a curious situation, it is

urged all alterations are precluded, has not made up his mind; and thinks it

precipitous to urge a decision in two days on a subject that took four Months.

If we have no right to amend, then we ought to give a silent passage; for if we

cannot alter, why should we deliberate. His opinion they should stand solely

upon the opinion of Convention.[13]

Clark argued:

The motion by Mr. Lee for amendments

will do injury by coming on the Journal, and therefore the house upon cool

reflection, will think it best to agree to send it out without agreeing. [14]

The opinions of James

Madison and Rufus King won out in the end and they were earnestly

supported by President Arthur St. Clair who, surprisingly, was and remains the only

foreign-born President of the United States —a circumstance outlawed by the new constitution. On September

30th, 1787, James Madison wrote George Washington, summing up the debate that occurred in the

United States in Congress Assembled’s U.S. Constitution sessions:

It was first urged that as the new

Constitution was more than an alteration of the Articles of Confederation under which Congress acted, and even subverted

these articles altogether, there was a Constitutional impropriety in their

taking any positive agency in the work.(1)

The answer given was that the Resolution of Congress in February had

recommended the Convention as the best mean of obtaining a firm national

Government; that as the powers of the Convention were defined by their

Commissions in nearly the same terms with the powers of Congress given by the

Confederation on the subject of alterations, Congress were not more restrained

from acceding to the new plan, than the Convention were from proposing it. If

the plan was within the powers of the Convention it was within those of

Congress; if beyond those powers, the same necessity which justified the

Convention would justify Congress; and a failure of Congress to Concur in what

was done, would imply either that the Convention had done wrong in exceeding

their powers, or that the Government proposed was in itself liable to

insuperable objections; that such an inference would be the more natural, as

Congress had never scrupled to recommend measures foreign to their

Constitutional functions, whenever the Public good seemed to require it; and

had in several instances, particularly in the establishment of the new Western

Governments, exercised assumed powers of a very high & delicate nature,

under motives infinitely less urgent than the present state of our affairs, if

any faith were due to the representations made by Congress themselves, echoed

by 12 States in the Union, and confirmed by the general voice of the People. An

attempt was made in the next place by Richard Henry Lee to amend the Act of the Convention before it

should go forth from Congress. He proposed a bill of Rights ; provision for

juries in civil cases & several other things corresponding with the ideas

of Col. M---;---;.(2) He was supported by Mr. Meriwether (3) Smith of this

State. It was contended that Congress had an undoubted right to insert

amendments, and that it was their duty to make use of it in a case where the

essential guards of liberty had been omitted.

On the other side the right of Congress

was not denied, but the inexpediency of exerting it was urged on the following

grounds. 1. That every circumstance indicated that the introduction of Congress

as a party to the reform was intended by the States merely as a matter of form

and respect 2. that it was evident from the contradictory objections which had

been expressed by the different members who had animadverted on the plan, that

a discussion of its merits would consume much time, without producing agreement

even among its adversaries. 3. that it was clearly the intention of the States

that the plan to be proposed should be the act of the Convention with the

assent of Congress, which could not be the case, if alterations were made, the

Convention being no longer in existence to adopt them. 4. that as the Act of

the Convention, when altered would instantly become the mere act of Congress,

and must be proposed by them as such, and of course be addressed to the

Legislatures, not conventions of the States, and require the ratification of

thirteen instead of nine States, and as the unaltered act would go forth to the

States directly from the Convention under the auspices of that Body---;Some

States might ratify one & some the other of the plans, and confusion &

disappointment be the least evils that could ensue.

These difficulties which at one time

threatened a serious division in Congress and popular alterations with the yeas

& nays on the journals, were at length fortunately terminated by the

following Resolution---;"Congress having recd. the Report of the

Convention lately assembled in Philadelphia, Resolved unanimously that the said

Report, (4) with the Resolutions & letter accompanying the same, be

transmitted to the several Legislatures, in order to be submitted to a

Convention of Delegates chosen in each State by the people thereof, in

conformity to the Resolves of the Convention made & provided in that case.[15]

This summary,

especially in point four, exemplifies James Madison’s legal position on

why it was constitutional to circumvent Article XIII of the Articles of

Confederation. I would argue, however, that George

Washington’s signature on the

new constitution carried more weight with the USCA and fellow Revolutionary War

General Arthur St. Clair’s Chair than the somewhat specious arguments made by

James Madison and his fellow delegates. The

September 28th, 1787, resolution passed by President Arthur St.

Clair’s USCA is recorded as:

Congress

having received the report of the Convention lately assembled in Philadelphia: Resolved Unanimously that

the said Report with the resolutions and letter accompanying the same be

transmitted to the several legislatures in Order to be submitted to a

convention of Delegates chosen in each state by the people thereof in

conformity to the resolves of the Convention made and provided in that case. [16]

In the final days of the USCA, Arthur St. Clair would be

named the first Northwest Territorial Governor under the Ordinance of

1787. Arthur St. Clair’s service as

Revolutionary War General, USCA President, and now Northwest Territorial

Governor, would all but be forgotten, however, by future generations of his

fellow Pennsylvanians. Ironically, on February 2nd (the anniversary

of St. Clair’s Presidency) Western Pennsylvanians do expertly market a groundhog

burrow emergence, less than 50 miles from the patriot’s 18th century

home. These citizen efforts have resulted in Punxsutawney Phil’s unprecedented

international rodent celebrity. It is

suggested here, to the mayor of Punxsutawney Pennsylvania, that perhaps a beam

of Phil’s national February 2nd spotlight might be shined on a

forgotten U.S. Presidency that just happened to birth the current Constitution

of the United States of America.

The historic 1787 USCA continued to conduct the nation’s

business into late October, voting to sell 1,000,000 acres of the Northwest

Territory to the Ohio Company. In its final November 1-2 session days, the 1787

USCA failed to achieve a quorum. On November 5th, 1787 Secretary

Charles Thomson called the new USCA to quorum but only five delegates,

representing three states, attended. It

was not until January 22, 1788 that the last USCA would form a quorum electing

Virginia Delegate Cyrus Griffin, President.

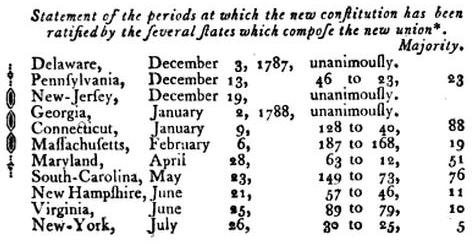

At the 1788 USCA session, the delegates were already

aware that five states (Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Georgia, and

Connecticut) had approved the Constitution

of 1787. The “Federalist Papers,”[17]

authored by James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay, made a most

persuasive case for ratification. Massachusetts would ratify the constitution on

February 6th, 1788, but Rhode Island, a month later, rejected

ratification by popular referendum. Maryland and South Carolina stayed the

federalist course and voted for ratification.

This set the stage for New Hampshire,[18] which

became the ninth state to ratify the new constitution on June 21, 1788, to lay

claim to the 57 to 47 vote that effectively terminated the Articles of

Confederation and its government.

Despite New Hampshire’s ratification meeting the new

constitution’s 2/3rds requirement, the USCA was unable to implement

the new government the following day as the Continental Congress did on March 2nd,

1781 after it had adopted the Articles of Confederation. The unicameral USCA was to be replaced by a

complex tripartite government with new officials. The ratifying states, by

virtue of the Constitution of 1787’s mechanisms,

required action by the USCA to establish a plan for the national election of

President as well as state elections of U.S Senators and House of

Representative members. Additionally, a

start date and location for the new Constitution

of 1787 government had to be established by the USCA. The plan to dissolve

the confederation and implement the Constitution

of 1787 government became the primary objective of the now lame-duck USCA

government. Meanwhile three states

(Virginia, New York, and North Carolina) had yet to vote on ratification so the

USCA bided its time adopting the 9th state’s ratification of the new

constitution.

In the Virginia ratification convention, James Madison found himself in direct opposition to Patrick

Henry, George Mason, William Grayson,

and future President James Monroe. These men and other

anti-federalists believed that the new constitution did not protect the

individual rights of citizens and created a central government that was too

powerful. On June 26, 1788 Madison and

his colleagues were able to secure the necessary votes by including in the ratification resolution “That

there be a Declaration or Bill of Rights asserting and securing from

encroachment the essential and unalienable Rights of the People in

some such manner as the following…”.[19] These recommended Virginia amendments

to the U.S. Constitution would eventually become the

framework for what we now call the “Bill

of Rights,”[20] the

first ten amendments to the Constitution.

Shortly after receiving the

good news of the Virginia ratification, the largest and 10th state to adopt the new

constitution, the USCA acted on New Hampshire’s ratification resolution,

resolving on July 2nd, 1788:

The State of New Hampshire having ratified the constitution transmitted

to them by the Act of the 28 of Septr last and transmitted to Congress their

ratification and the same being read, the president reminded Congress that this

was the ninth ratification transmitted and laid before them, whereupon, on

Motion of Mr. Clarke seconded by Mr. Edwards - Ordered That the ratifications

of the constitution of the United States transmitted to Congress be referred to

a comee to examine the same and report an Act to Congress for putting the said

constitution into operation in pursuance of the resolutions of the late federal

Convention.[21]

The committee consisted of

Edward Carrington, Pierpont Edwards, Abraham Baldwin, Samuel Allyne Otis and

Thomas Tudor Tucker. They reported and

made recommendations to Congress on July 8th, 9th, 14th

and 28th but no plan was adopted for the transition. The July USCA

deliberations on how to implement the new U.S. Constitution were overshadowed

by their host state’s ratifying convention

being held in Poughkeepsie, New York.

If the convention failed to ratify the Constitution of 1787, the USCA could not consider convening the new

government in their current seat, New York City. Thus a plan could not be debated, let alone

adopted, until the ratification votes from the New York Convention were

tallied.

Federalist leaders, John Jay,

Robert R. Livingston, and Alexander Hamilton encountered stiff opposition to the new

constitution in Poughkeepsie.

Jay advocated ratification, reminding

the Convention that:

… the direction of general and national

affairs is submitted to a single body of men, viz. the congress. They may make

war; but are not empowered to raise men or money to carry it on. They may make

peace; but without power to see the terms of it observed. They may form

alliances, but without ability to comply with the stipulations on their part.

They may enter into treaties of commerce; but without power to enforce them at

home or abroad. They may borrow money; but without having the means of

re-payment. They may partly regulate commerce; but without authority to execute

their ordinances. They may appoint ministers and other officers of trust; but

without power to try or punish them for misdemeanors. They may resolve; but cannot

execute either with dispatch or with secrecy. In short, they may consul and

deliberate and recommend and make requisitions; and they who please, may read

them. From this new and wonderful system

of government, it has come to pass, that almost every national object of every

kind is, at this day, unprovided for; and other nations, taking the advantage

of its imbecility, are daily multiplying commercial restraints upon us. [22]

Livingston, upon learning of

New Hampshire’s ratification remarked, “The

Confederation was now dissolved. The question before the committee was now a

question of policy and expediency.”[23]

News that Virginia, the home state of George Washington, had also ratified

the new constitution all but assured the demise of the Articles of Confederation

Republic with or without New York. Jay,

Livingston, Hamilton, and their supporters therefore were able to eke out a

razor thin victory with a 30 to 27 ratification vote whose convention also

proposed amendments to the new constitution including:

That the People have an equal, natural

and unalienable right, freely and peaceably to Exercise their Religion

according to the dictates of Conscience, and that no Religious Sect or Society

ought to be favoured or established by Law in preference of others. That the

People have a right to keep and bear Arms; that a well-regulated Militia,

including the body of the People capable of bearing Arms, is the proper,

natural and safe defence of a free State; … That the People have a right peaceably to assemble together

to consult for their common good, or to instruct their Representatives; and

that every person has a right to Petition or apply to the Legislature for

redress of Grievances.-That the Freedom of the Press ought not to be violated

or restrained.[24]

During the New York

Convention, North Carolina delegates had assembled in Hillsborough to consider

ratifying the Constitution of 1787. Federalists,

led by James Iredell, Sr., struggled to mitigate Antifederalists' fears that

the Constitution of 1787 would ultimately

concentrate power at the national level permitting the federal government to

chip away at states' rights and individual liberties. The abuse of power arising

from empowering a central government to levy taxes, appoint government

officials, and institute a strong court system was of particular concern to

Antifederalists leaders Willie Jones, Samuel Spencer, and Timothy Bloodworth. Antifederalist

William Gowdy of Guilford County summed up the majority’s opinion in the

debates, stating:

Its intent is a concession of power, on

the part of the people, to their rulers. We know that private interest governs

mankind generally. Power belongs originally to the people; but if rulers be not

well guarded, that power may be usurped from them. People ought to be cautious

in giving away power.[25]

The North Carolina

delegates, who overwhelming distrusted the proposed centralized authority, adjourned on August 4th

after they had drafted a "Declaration

of Rights" and a list of "Amendments

to the Constitution." Unlike

New York and Virginia, these members voted "neither

to ratify nor reject the Constitution proposed for the government of the United

States." James Madison reported

to his father:

We just learn the fate of the

Constitution in N. Carolina. Rho. Island is however her only associate in the

opposition and it will be hard indeed if those two States should endanger a

system which has been ratified by the eleven others. Congress has not yet

finally settled the arrangements for putting the new Government in operation.

The place for its first meeting creates the difficulty. The Eastern States with

N. York contend for this City. Most of the other States insist on a more

central position.[26]

The dies were now cast,

eleven states, not thirteen, would form a new United American Republic, We The People of the United States of

America.

August 1788 Printing of the “More or

Less” 11 United States Ratification Statistics

All throughout August and

into September, the USCA debated the implementation of the new U.S.

Constitution. James Madison wrote Thomas

Jefferson, who was serving in France as U.S. Minister:

Congress have not yet decided on the

arrangements for inaugurating the new Government. The place of its first

meeting continues to divide the Northern & Southern members, though with a

few exceptions to this general description of the parties. The departure of

Rhode Island, and the refusal of North Carolina in consequence of the late

event there to vote in the question, threatens a disagreeable issue to the business,

there being now an apparent impossibility of obtaining seven States for any one

place. The three Eastern States & New York, reinforced by South Carolina,

and as yet by New Jersey, give a plurality of votes in favor of this City [New

York]. The advocates for a more central

position however though less numerous, seemed very determined not to yield to

what they call a shameful partiality to one extremity of the Continent.[27]

The start date for the Fourth United American Republic also

eludes the test of general acceptance by the political and academic

communities. After challenging Robert C. Byrd for his U.S. Senate Seat in 1994,

he and I came together on his idea of marking September 17th, each

year, as the anniversary of the signing of the Constitution of 1787. Byrd’s

bill was enacted by Congress with a provision requiring schools and federal

agencies to set aside time to study the Constitution on or about the

anniversary date. September 17th,

as noted in the last chapter, marks the Philadelphia Convention’s completion of

the Constitution of 1787 which was curried to New York, debated by the USCA and

sent to the states on September 28, 1787, unchanged by delegates. These

events, however, do not mark the start of the Fourth American United Republic. The Constitution of 1787, which ultimately

formed the current American United

Republic, required ratification by nine states before the USCA would be forced

to dissolve itself and implement a plan of installing the new tripartite federal

government.

On September 13th,

1788 the USCA finally agreed to keep the Constitution

of 1787 United States seat of government in New York. The USCA then approved a plan to dissolve itself and implement

the Constitution of 1787. Congress resolved that March 4th,

1789 would be the starting date of the current and Fourth United American

Republic:

Whereas the Convention assembled in

Philadelphia pursuant to the resolution of Congress of the

21st of Feby, 1787 did on the 17th. of Sept of the same year report to the

United States in Congress assembled a constitution for the people of the United

States, whereupon Congress on the 28 of the same Sept did resolve unanimously

"That the said report with the resolutions and letter accompanying the

same be transmitted to the several legislatures in order to be submitted to a

convention of Delegates chosen in each state by the people thereof in

conformity to the resolves of the convention made and provided in that

case" And whereas the constitution so reported by the Convention and by

Congress transmitted to the several legislatures has been ratified in the

manner therein declared to be sufficient for the establishment of the same and

such ratifications duly authenticated have been received by Congress and are

filed in the Office of the Secretary therefore Resolved That the first

Wednesday in Jany next be the day for appointing Electors in the several

states, which before the said day shall have ratified the said constitution;

that the first Wednesday in feby next be

the day for the electors to assemble in their respective states and vote for a

president; and that the first Wednesday in March next be the time and the

present seat of Congress the place for commencing proceedings under the said

constitution.[28]

On October 2nd

Congress debated where to relocate Secretary Thomson’s office and the nation’s

records. The USCA, in an arrangement to

keep the seat of government in New York, exacted an agreement from Mayor James

Duane and the New York City council to completely renovate the building they

were currently occupying for the new tripartite government. The extensive work that was planned required

the USCA to find other quarters for Thomson, federal staff, congressional

meetings, and the nation’s records. The War

Office and Department of Foreign Affairs had occupied six rooms at Fraunces

Tavern since 1785. The initial two year lease had expired in May, 1787, but the

USCA had renewed the space for another year, and had added some Treasury

Offices. Incredibly, the USCA whose

republic was founded by a Congress that first caucused in a Philadelphia Tavern

was considering leasing this New York Tavern as the final seat of their failed

unicameral government experiment. On

October 2nd, 1788, the USCA resolved:

The committee consisting of Mr [Thomas

Tudor] Tucker, Mr [John] Parker, and Mr [Abraham] Clark to whom was referred a

letter from the Mayor of the city of New York to the Delegates having reported,

That it appears from the letter referred to them, that the repairs and

alterations intended to be made in the buildings in which Congress at present

Assemble, will render it highly inconvenient for them to continue business

therein, that it will therefore be necessary to provide some other place for

their accommodation, the committee having made enquiry find no place more

proper for this purpose than the two Apartments now appropriated for the Office

of Foreign Affairs. They therefore recommend that the said Apartments be

immediately prepared for the reception of Congress and the papers of the

Secretary. Resolved, that

Congress agree to the said report. [29]

On October 6, 1788,

renovations began on the building that would be called thereafter, Federal

Hall. The USCA moved their offices to Fraunces Tavern and reconvened on October

8th and on motion by Henry Lee that was seconded by John Armstrong

Congress resolved:

That considering the peculiar

circumstances attending the case of Muscoe Livingston, late a Lieutenant in the

navy of the United States, in the settlement of his accounts, Resolved, that

the Commissioner for the marine department adjust the said account, any

resolution of Congress to the contrary notwithstanding.[30]

The rest of the

session was spent reviewing Governor Arthur St. Clair’s letter and five

enclosures from the Northwest Territory. On the 9th they assembled

as before and passed a resolution permitting

the Board of Treasury to satisfy a lottery claim providing that the

beneficiaries “do give security that no

further Claim on account of said Prize Ticket shall be made upon the United

States by the Heirs, Executors or Administrators of the said deceased, Gail, or

either of them.”[31]

On October 10th, 1788,

Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Virginia, North

Carolina and South Carolina assembled along with only under representation (one

delegate) from New Hampshire, from Rhode Island Delaware and Maryland in a USCA

quorum for the last time. Only Georgia,

as with the first 1774 Continental Congress, failed to send delegates. The USCA in their last official act

suspended the work of the commissioners who had been appointed to settle the

states' federal accounts. The USCA’s

last motion was made by Abraham Clark and seconded by Hugh Williamson,

That the Secretary at War be and he

hereby is directed to forbear issuing warrants for bounties of land to such of

the officers of the late army who have neglected to account for monies by them

received as pay masters of Regiments, or for recruiting or other public

service, until such officers respectively shall have settled their accounts

with the commissioner of army accounts, or others legally authorized to settle

the same, and have paid the balances that may be found due from them, into the

treasury of the United States, anything in the land ordinance passed the 9th .

day of July 1788 to the contrary notwithstanding.

The Delegates tabled

the measure, “the question was lost” and

USCA adjourned. Despite the adjournment

and several unsuccessful attempts to form more quorums, it was necessary for

some delegates to serve in New York, including President Griffin, and conduct

the nation's business until the new government took office on March 4th,

1789. Cyrus Griffin, John Brown, John Dawson, James Madison, and Mann Page were

elected on October 31st, 1788 as Delegates to the USCA from

Virginia. Griffin wrote in November:

Be

so obliging to inform the House of Delegates that I shall continue in New York

to execute the important Trust with which the general Assembly is pleased to

honor me. I receive this further Mark of their Confidence with gratitude and

pleasure & will endeavor to answer the expectations of my Country.[32]

The USCA Journals report the final days of the Third

United American Republic as thus:

October 13-16 fails to achieve quorum. October 21, 1788 Two

states attended namely Massachusetts and South Carolina and from New Hampshire

Nicholas Gilman from Connecticut Benjamin Huntington from Pennsylvania William

Irvine from Maryland Benjamin Contee from Virginia Cyrus Griffin and from North

Carolina Hugh Williamson. October 22-November 1, 1788 there appear attended

occasionally from New Hampshire Nicholas Gilman, from Massachusetts Samuel A

Otis and George Thatcher, from Rhode island Peleg Arnold, from Connecticut

Benjamin Huntington and Pierpont Edwards, from New Jersey Jonathan Dayton, from

Pennsylvania William Irvine, from Maryland Benjamin Contee, from Virginia Cyrus

Griffin, from North Carolina Hugh Williamson, and from South Carolina Daniel

Huger John Parker and Thomas Tudor Tucker. November 3, 1788 Pursuant to

the Articles of the Confederation only two Gentlemen attended Benjamin Contee

for Maryland and Hugh Williamson for North Carolina. November 15, 1788 Cyrus

Griffin from Virginia attended; December 1, 1788 John Dawson from Virginia and;

December 6, 1788 Nicholas Eveleigh from South Carolina attended; December 11,

1788 Jonathan Dayton from New Jersey attended; December 15, 1788 Thomas Tudor

Tucker from South Carolina; December 30, 1788 Samuel A Otis from Massachusetts;

January 1, 1789 James R. Reid from Pennsylvania, Robert Barnwell from South

Carolina; January 8, 1789 Abraham Clarke from New Jersey; January 10, 1789

Trenche Coxe from Pennsylvania; January 26, 1789 Nathaniel Gorham from Massachusetts; January 29, 1789 George Thatcher from

Massachusetts; February 6, 1789 David Ross from Maryland; February 12, 1789

John Gardner from Rhode island. February 18, 1789 David Gelston from New York

February 19, 1789 Nicholas Gilman from New Hampshire; March 2 Philip Pell from

New York.

Although the start date of

the Fourth American Republic was set by the USCA as March 4th, 1789,

the first bicameral congress of the new republic did not convene due to quorum

challenges. It would not be until April

1st, 1789, that the U.S. House of Representatives was able to

achieve a quorum. Five days later, on April 6th, the U.S. Senate

achieved a quorum and elected its officers.

The Senate also tallied and certified the electoral votes from ten

states[33]

for President and Vice President. Washington vote counts in Delaware (John Jay),

Maryland (Robert H. Harrison), New Hampshire (John Adams) and Massachusetts

(John Adams) all resulted in a tie because each elector was able to vote for

two Presidents. Washington, however, handily won the election with 69 electoral

votes. John Adams came in second with 34

votes and under the Constitution

of 1787 was

awarded the office of Vice President.[34]

The legislation passed by the First federal bicameral Congress and signed by President Washington in 1789:

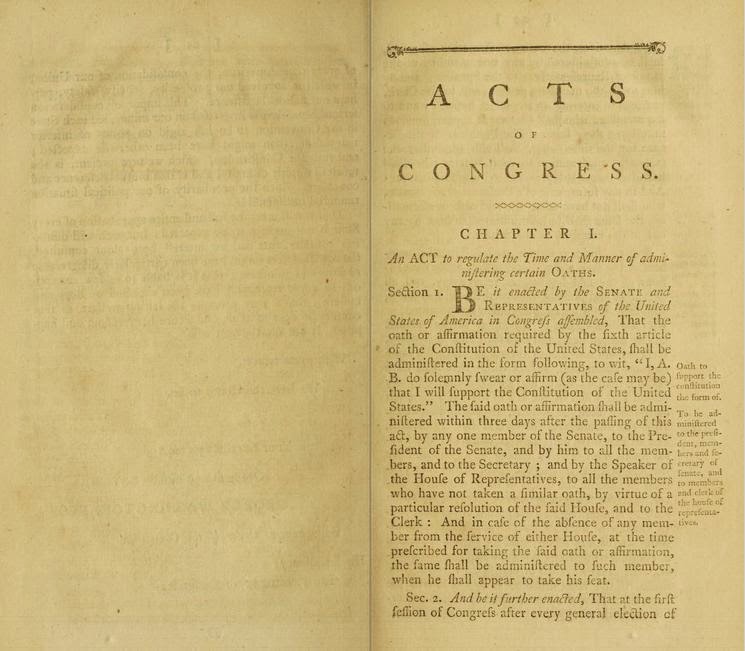

- On June 1st, 1789: An Act to regulate the Time and Manner of administering certain Oaths was the first law passed by the United States Congress and signed into law by President George Washington after the ratification of the U.S. Constitution. Parts of the law still remain on the books;

- On July 4th, 1789 An Act for laying a Duty on Goods, Wares, and Merchandises imported into the United States was passed to immediately establish the tariff as a regular source of revenue for the federal government and as a protection of domestic manufacture;

- July 20th., 1789 An Act imposing Duties on Tonnage is passed and laid out various rates of duty on the tonnage of ships and vessels entered in the United States from foreign countries;

- On July 27th, 1789 An Act for Establishing an Executive Department, to be Denominated The Department of Foreign Affairs was passed. John Jay, Articles of Confederation Secretary of Foreign Affairs turned down reappointment but agreed to serve as acting Secretary until a Presidential appointment was confirmed. During the enactment of this bill a debate arose as to the power of removal of the Foreign Secretary. One side contended that the power belonged to the President, by virtue of the executive powers of the Government vested in him by the constitution. The other side maintained that the power of removal should be exercised by the President, conjointly with the Senate. The important question was decided by Congress in favor of the President's power to remove the heads of all these Departments, on the ground that they are Executive Departments;

- On July 31st, 1789 An Act to regulate the Collection of the Duties imposed by law on the tonnage of ships or vessels, and on goods, wares and merchandises imported into the United States was passed establishing ports of entry in each of the eleven states where duties were to be collected. North Carolina and Rhode Island, who had not ratified the new constitution, were subject to same goods’ duties as from foreign countries. Be it therefore further enacted, That all goods, wares and merchandise not of their own growth or manufacture, which shall be imported from either of the said two States of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, or North Carolina, into any other port or place within the limits of the United States, as settled by the late treaty of peace, shall be subject to the like duties, seizures and forfeitures, as goods, wares or merchandise imported from any State or country without the said limits;

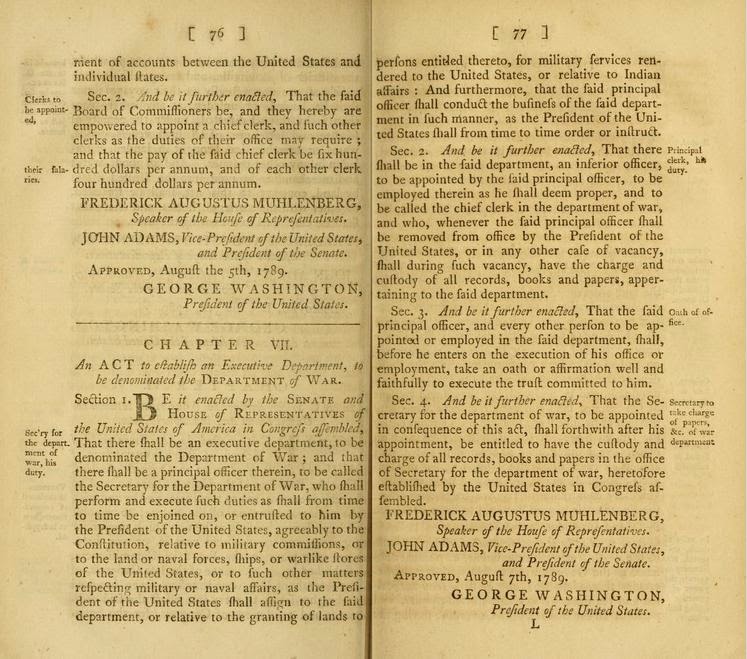

- On August 5th, 1789 An Act for settling the Accounts between the United States and individual States was passed appointing and paying commissioners to carry into effect the May 7th, 1787 ordinance and subsequent resolutions established by the USCA “… for the settlement of accounts between the United States and individual States;”

- On August 7th, 1789 An Act to establish an Executive Department, to be denominated the Department of War was passed. Former USCA Secretary of War Henry Knox was re-appointed by President Washington and confirmed by the U.S. Senate. The Department of War oversaw all military affairs until Congress created a separate Navy Department in 1798. The National Security Act, passed by Congress in 1947, designated departments for the Army, Navy, and the Air Force. A National Military Establishment, renamed the Department of Defense in 1949, administered these departments;

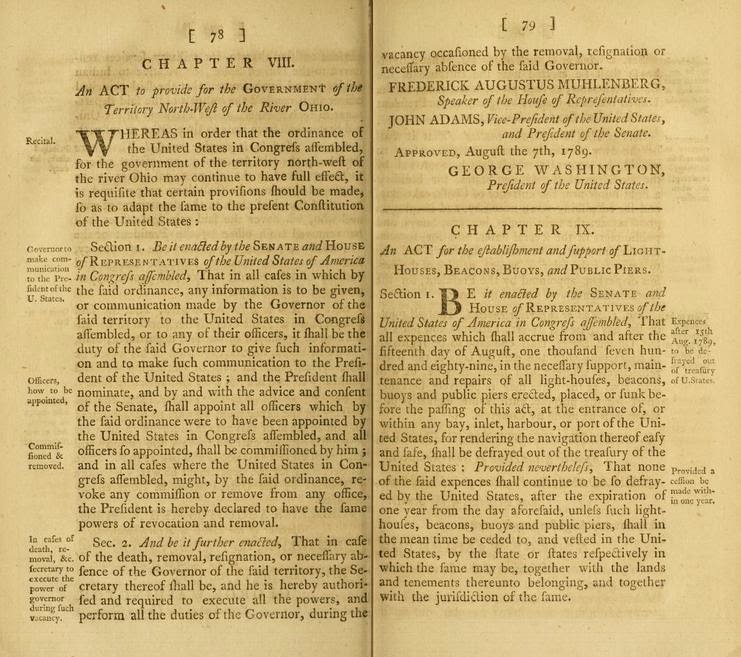

- Also on August 7th, 1789 An Act to provide for the Government of the Territory Northwest of the river Ohio was passed. This bill was the reenactment of the Northwest Ordinance passed by the USCA in July 1787 so that “… may continue to have full effect, it is requisite that certain provisions should be made, so as to adapt the same to the present Constitution of the United States.” Former USCA Governor Arthur St. Clair was re-appointed by President Washington and confirmed by the U.S. Senate;

- On August 20th, 1789 An Act providing for the Expenses which may attend Negotiations or Treaties with the Indian Tribes, and the appointment of Commissioners for managing the same was passed;

- On September 1st, 1789 An Act for Registering and Clearing Vessels, Regulating the Coasting Trade, and for other purposes was passed providing for the licensing and enrollment of vessels engaged in navigation and trade;

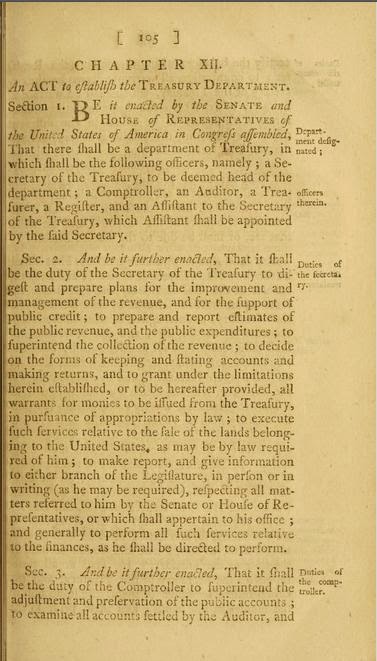

- On September 2nd, 1789 An Act to establish the Treasury Department was passed. The act assigns duties to the Secretary, Comptroller, Auditor, Treasurer, Register, and Assistant to the Secretary. It prohibits persons appointed under the act from engaging in specified business transactions and prescribes penalties for so doing. It also provides that if information from a person other than a public prosecutor is the basis for the conviction, that person shall receive half the fine. Alexander Hamilton was appointed Secretary of the Treasury by President Washington and was confirmed the same day by the U.S. Senate;

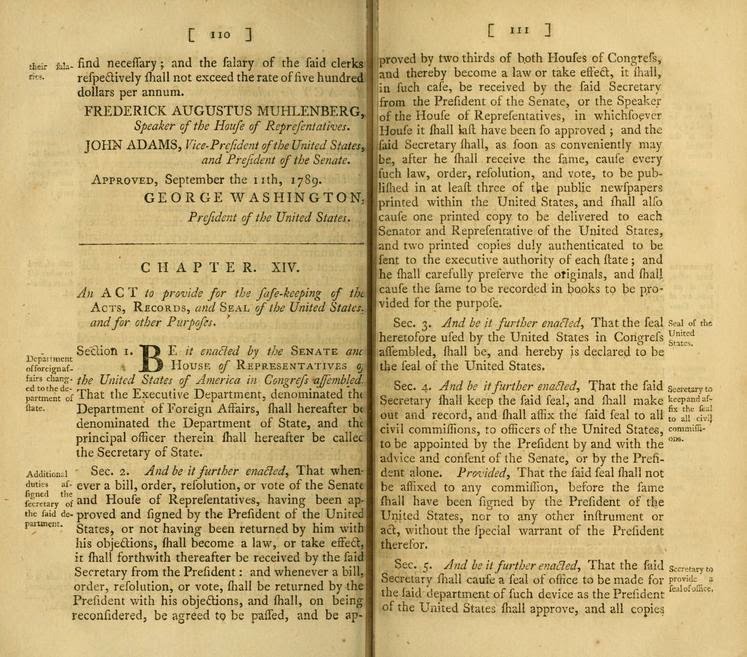

- On September 11th, 1789 An Act for establishing the Salaries of the Executive Officers of Government, with their Assistants and Clerks was passed;

- On September 15th, 1789 An Act to provide for the safe-keeping of the Acts, Records and Seal of the United States, and for other purposes was passed. This law changed the name of the Department of Foreign Affairs to the Department of State because certain domestic duties were assigned to the agency. These included: Receipt, publication, distribution, and preservation of the laws of the United States; Preparation, sealing, and recording of the commissions of Presidential appointees; Preparation and authentication of copies of records and authentication of copies under the Department's seal; Custody of the Great Seal of the United States; Custody of the records of the former Secretary of the Continental Congress, except for those of the Treasury and War Departments. Thomas Jefferson was appointed by President Washington September 25, 1789 and confirmed by the U.S. Senate the following day. Chief Justice John Jay served as Acting Secretary of State until Secretary Jefferson returned from France. Other domestic duties for which the Department was responsible at various times included issuance of patents on inventions, publication of the census returns, management of the mint, control of copyrights, and regulation of immigration;

- On September 22nd, 1789 An Act for the temporary establishment of the Post-Office was passed. “That there shall be appointed a Postmaster General; his powers and salary and the compensation to the assistant or clerk and deputies which he may appoint, and the regulations of the post-office shall be the same as they last were under the resolutions and ordinances of the late Congress.” Samuel Osgood was appointed Postmaster General by President Washington on September 26th, 1789 and confirmed by the U.S. Senate the following day;

- Also on September 22nd, 1789 An Act for allowing Compensation to the Members of the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States, and to the Officers of both Houses was passed. Unlike the USCA, whose members were paid by their respective states, the congressmen were paid $6.00 a day from the new federal treasury;

- On September 23rd, 1789 An Act for allowing certain Compensation to the Judges of the Supreme and other Courts, and to the Attorney General of the United States was passed with salaries ranging from $4,000 for the Chief Justice to $800 for the Delaware Federal District Judge. The Attorney General’s salary was set at $1,500 while Associate Justices of the Supreme Court were paid $3,500;

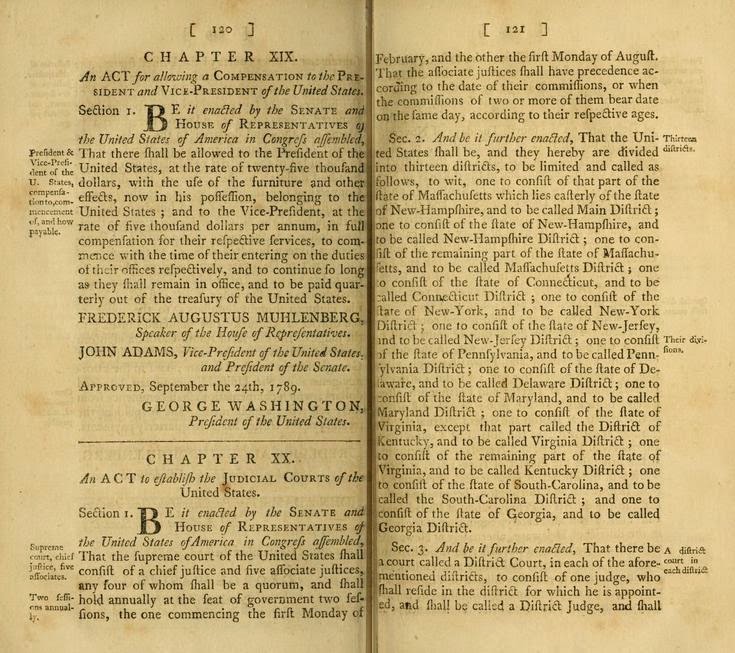

- On September 24th, 1789 An Act for allowing a compensation to the President and Vice President of the United States was passed with the salaries of $25,000[3] and $5,000 respectively.

- On September 24th, 1789 the Judiciary Act was established. The Act calls for the organization of the U.S. federal court system, which had been sketched only in general terms in the U.S. Constitution. The act established a three-part judiciary that was made up of district courts, circuit courts, and the Supreme Court. The act also outlined the structure and jurisdiction of each branch. John Jay was appointed U.S. Chief Justice and Edmond Randolph appointed Attorney General by President Washington on September 24th, 1789 and the two were confirmed by the U.S. Senate on September 26th.

- On September 25th, Congress proposed the Bill of Rights. The amendments were introduced by James Madison as a series of legislative articles. They were adopted by the House of Representatives on August 21, 1789, formally proposed by joint resolution of Congress on September 25, 1789, and came into effect as Constitutional Amendments on December 15, 1791, through the process of ratification by three-fourths of the states. While twelve amendments were proposed by Congress, only ten were originally ratified by the states. Of the remaining two, one was adopted 203 years later as the Twenty-seventh Amendment, and the other technically remains pending before the states.

- On September 29th, 1789 An Act to regulate Processes in the Courts of the United States was passed authorizing the courts of the United States to issue writs of execution as well as other writs;

- On September 29th, 1789 An Act making Appropriations for the Service of the present year was passed. Specifically the bill provided for “a sum not exceeding two hundred and sixteen thousand dollars for defraying the expenses of the civil list, under the late and present government; a sum not exceeding one hundred and thirty-seven thousand dollars for defraying the expenses of the department of war; a sum not exceeding one hundred and ninety thousand dollars for discharging the warrants issued by the late board of treasury, and remaining unsatisfied; and a sum not exceeding ninety-six thousand dollars for paying the pensions to invalids”;

- On September 29th, 1789 An Act providing for the payment of the Invalid Pensioners of the United States was passed. The act specified “that the military pensions which have been granted and paid by the states respectively, in pursuance of the acts of the United States in Congress assembled, to the invalids who were wounded and disabled during the late war, shall be continued and paid by the United States, from the fourth day of March last, for the space of one year, under such regulations as the President of the United States may direct”;

- On September 29th, 1789 An Act to recognize and adapt the Constitution of the United States the establishment of the Troops raised under the Resolves of the United States in Congress assembled, and for other purposes therein mentioned was passed. The act specified “that the establishment contained in the resolve of the late Congress of the third day of October, one thousand seven hundred and eighty-seven, except as to the mode of appointing the officers, and also as is herein after provided, be, and the same is hereby recognized to be the establishment for the troops in the service of the United States;”

- On September 29th, 1789 An Act to alter the Time for the Next Meeting of Congress was passed adjourning the 1st Federal Bicameral Congress until January 5, 1790

|

National Collegiate Honor’s Council Partners in the Park Independence Hall Class of 2017 students at Federal Hall National Historic Park with Ranger holding the 1789 Acts of Congress opened to the 12 Amendment Joint Resolution of Congress issued September 25th, 1789. The only amendment in the "Bill of Rights" that was not ratified is Article the First, which is still pending before Congress. Cintly is holding an Arthur St. Clair signed Northwest Territory document, Imani is holding the First Bicameral Congressional Act establishing the U.S. Department of State and Rachael is holding a 1788 John Jay letter sent to the Governor of Connecticut, Samuel Huntington, transmitting a treaty with France. – Primary Sources courtesy of Historic.us |

[1] Rhode Island

sent no delegates.

[2] South

Carolina Delegate Henry Laurens, in a final constitutional

act, voted against Virginia's attempt to gain more power

in the federal government based on population. Specifically, Virginia's

amendment to the Articles of Confederation proposed that the nine votes

necessary to determine matters of importance in the USCA must come from only the states that contained

a majority of the white population.

[3] The New

Jersey Plan was the developed by the small States and

named after N.J. Delegate William Paterson who presented it on the convention

floor.

[4] Max Farrand, The records of the Federal convention of

1787, Volume 1. New Haven: Yale

University Press, 1911, p. 444

[5] George

Washington, Convention President, Plan of the New Federal Government,

Printed by Robert Smith, Philadelphia: 1787, Original Document, Stan

Klos Collection.

[7] The

Confederate States of America (1861-1865) was a government created by eleven

Southern states that had declared their secession from the United States.

Secessionists argued that the United States Constitution was a compact among

states, an agreement which each state could abandon without consultation. The

Union government rejected secession as illegal. A War ensued and the

Confederacy was tactically lost with General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern

Virginia surrender at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, on April 9, 1865. President Jefferson Davis was capture the

following month and by the end of June 1865 all CSA forces had surrendered.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[16] JCC, 1774-1789, September 28, 1787

[17] The

Federalist Papers are a series of 85 essays promoting the ratification of the U.S. Constitution

of 1787. They were written by

Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison. Seventy-seven of the essays

were published serially as articles in the Independent

Journal and the New York Packet

between October 1787 and August 1788. A compilation of these and eight others,

called The Federalist was published by J. and A. McLean in 1788. The title "Federalist Papers" did

not emerge in the U.S. lexicon until the early twentieth century.

[18] Philip Robert

Dillon, American Anniversaries: Every Day

in the Year, Presenting Seven Hundred and Fifty Events in United States History,

from the Discovery of America to the Present Day, The Philip R. Dillon: New York 1918

[19] Ratification of the Constitution by the

State of Virginia; June 26, 1788, Avalon project, Yale University,

http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/ratva.asp 2011

[20] The Bill of Rights was the first ten amendments to the United

States Constitution. They were introduced by Representative James Madison to the U.S. House in 1789 as a series of 17

articles. Twelve amendments were approved by Congress but only ten came into

effect on December 15, 1791, when they were ratified by three-fourths of the

States.

[22] James Hardie, The Description of the City of New York, A Brief Account and Most Remarkable Events,

Which Have Occurred in Its History, New York: S. Marks Publisher, : 1827, p. 113

[23]Jonathan

Elliot and James Madison, The debates in

the several State conventions on the adoption of the federal Constitution, as

recommended by the general convention at Philadelphia, in 1787: Together with

the Journal of the federal convention, Luther Martin's letter, Yates's minutes,

Congressional opinions, Virginia and Kentucky resolutions of '98-'99, and other

illustrations of the Constitution, J. B. Lippincott company, 1891, Volume

II, P. 320.

[24] Ratification of the Constitution by the

State of New York; July 26, 1788, Avalon project, Yale University,

http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/ratny.asp 2012

[25]Jonathan

Elliot and James Madison, The debates in

the several State conventions on the adoption of the federal Constitution, as

recommended by the general convention at Philadelphia, in 1787: Together with

the Journal of the federal convention, Luther Martin's letter, Yates's minutes,

Congressional opinions, Virginia and Kentucky resolutions of '98-'99, and other

illustrations of the Constitution, J. B. Lippincott company, 1891, Volume

IV, Page 13.

[26] LDC, 1774-1789, James Madison, Jr. to

James Madison, August 18, 1788

[27] LDC, 1774-1789, James Madison to Thomas

Jefferson, August 23, 1788.

[33] Rhode Island

and North Carolina still had not ratified the Constitution of 1787. The New York legislature could not agree

on a method for choosing electors and did not participate in the first

presidential election.

[34] In 1789 the

electors voted only for the office of President rather than for both President

and Vice President. Each elector was allowed to vote for two people for the

U.S. Presidency. The person receiving the greatest number of votes became

President while the second largest vote candidate became Vice President. If no

candidate received a majority of votes, then the House of Representatives would

choose among the five highest top candidates, with each state getting one vote.

In the presidential election of 1800 Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr tied at 73

votes. It took the House of Representatives 36 ballots to finally choose

Jefferson over Burr who became Vice President.

This contentious affair resulted in the adoption of the Twelfth

Amendment in 1804, which directed the electors to use separate ballots to vote

for the President and Vice President. While this solved the problem at hand, it

ultimately had the effect of lowering the prestige of the Vice Presidency, as

the office was no longer for the leading challenger for the Presidency.

Continental Congress of the United States Presidents

July 2, 1776 to February 28, 1781

202-239-1774 | Office

202-239-0037 | FAX

Dr. Naomi and Stanley Yavneh Klos, Principals

The Congressional Evolution of the United States of America

Continental Congress of the United Colonies Presidents

Continental Congress of the United Colonies Presidents

Sept. 5, 1774 to July 1, 1776

September 5, 1774

|

October 22, 1774

| |

October 22, 1774

|

October 26, 1774

| |

May 20, 1775

|

May 24, 1775

| |

May 25, 1775

|

July 1, 1776

|

Commander-in-Chief United Colonies & States of America

George Washington: June 15, 1775 - December 23, 1783

Continental Congress of the United States Presidents

July 2, 1776 to February 28, 1781

July 2, 1776

|

October 29, 1777

| |

November 1, 1777

|

December 9, 1778

| |

December 10, 1778

|

September 28, 1779

| |

September 29, 1779

|

February 28, 1781

|

Presidents of the United States in Congress Assembled

March 1, 1781 to March 3, 1789

March 1, 1781 to March 3, 1789

March 1, 1781

|

July 6, 1781

| |

July 10, 1781

|

Declined Office

| |

July 10, 1781

|

November 4, 1781

| |

November 5, 1781

|

November 3, 1782

| |

November 4, 1782

|

November 2, 1783

| |

November 3, 1783

|

June 3, 1784

| |

November 30, 1784

|

November 22, 1785

| |

November 23, 1785

|

June 5, 1786

| |

June 6, 1786

|

February 1, 1787

| |

February 2, 1787

|

January 21, 1788

| |

January 22, 1788

|

January 21, 1789

|

Presidents of the United States of America

D-Democratic Party, F-Federalist Party, I-Independent, R-Republican Party, R* Republican Party of Jefferson & W-Whig Party

(1789-1797)

|

(1933-1945)

| |

(1865-1869)

| ||

(1797-1801)

|

(1945-1953)

| |

(1869-1877)

| ||

(1801-1809)

|

(1953-1961)

| |

(1877-1881)

| ||

(1809-1817)

|

(1961-1963)

| |

(1881 - 1881)

| ||

(1817-1825)

|

(1963-1969)

| |

(1881-1885)

| ||

(1825-1829)

|

(1969-1974)

| |

(1885-1889)

| ||

(1829-1837)

|

(1973-1974)

| |

(1889-1893)

| ||

(1837-1841)

|

(1977-1981)

| |

(1893-1897)

| ||

(1841-1841)

|

(1981-1989)

| |

(1897-1901)

| ||

(1841-1845)

|

(1989-1993)

| |

(1901-1909)

| ||

(1845-1849)

|

(1993-2001)

| |

(1909-1913)

| ||

(1849-1850)

|

(2001-2009)

| |

(1913-1921)

| ||

(1850-1853)

|

(2009-2017)

| |

(1921-1923)

| ||

(1853-1857)

|

(20017-Present)

| |

(1923-1929)

|

*Confederate States of America

| |

(1857-1861)

| ||

(1929-1933)

| ||

(1861-1865)

|

United Colonies Continental Congress

|

President

|

18th Century Term

|

Age

|

Elizabeth "Betty" Harrison Randolph (1745-1783)

|

09/05/74 – 10/22/74

|

29

| |

Mary Williams Middleton (1741- 1761) Deceased

|

Henry Middleton

|

10/22–26/74

|

n/a

|

Elizabeth "Betty" Harrison Randolph (1745–1783)

|

05/20/ 75 - 05/24/75

|

30

| |

Dorothy Quincy Hancock Scott (1747-1830)

|

05/25/75 – 07/01/76

|

28

| |

United States Continental Congress

|

President

|

Term

|

Age

|

Dorothy Quincy Hancock Scott (1747-1830)

|

07/02/76 – 10/29/77

|

29

| |

Eleanor Ball Laurens (1731- 1770) Deceased

|

Henry Laurens

|

11/01/77 – 12/09/78

|

n/a

|

Sarah Livingston Jay (1756-1802)

|

12/ 10/78 – 09/28/78

|

21

| |

Martha Huntington (1738/39–1794)

|

09/29/79 – 02/28/81

|

41

| |

United States in Congress Assembled

|

President

|

Term

|

Age

|

Martha Huntington (1738/39–1794)

|

03/01/81 – 07/06/81

|

42

| |

Sarah Armitage McKean (1756-1820)

|

07/10/81 – 11/04/81

|

25

| |

Jane Contee Hanson (1726-1812)

|

11/05/81 - 11/03/82

|

55

| |

Hannah Stockton Boudinot (1736-1808)

|

11/03/82 - 11/02/83

|

46

| |

Sarah Morris Mifflin (1747-1790)

|

11/03/83 - 11/02/84

|

36

| |

Anne Gaskins Pinkard Lee (1738-1796)

|

11/20/84 - 11/19/85

|

46

| |

Dorothy Quincy Hancock Scott (1747-1830)

|

11/23/85 – 06/06/86

|

38

| |

Rebecca Call Gorham (1744-1812)

|

06/06/86 - 02/01/87

|

42

| |

Phoebe Bayard St. Clair (1743-1818)

|

02/02/87 - 01/21/88

|

43

| |

Christina Stuart Griffin (1751-1807)

|

01/22/88 - 01/29/89

|

36

|

Constitution of 1787

First Ladies |

President

|

Term

|

Age

|

April 30, 1789 – March 4, 1797

|

57

| ||

March 4, 1797 – March 4, 1801

|

52

| ||

Martha Wayles Jefferson Deceased

|

September 6, 1782 (Aged 33)

|

n/a

| |

March 4, 1809 – March 4, 1817

|

40

| ||

March 4, 1817 – March 4, 1825

|

48

| ||

March 4, 1825 – March 4, 1829

|

50

| ||

December 22, 1828 (aged 61)

|

n/a

| ||

February 5, 1819 (aged 35)

|

n/a

| ||

March 4, 1841 – April 4, 1841

|

65

| ||

April 4, 1841 – September 10, 1842

|

50

| ||

June 26, 1844 – March 4, 1845

|

23

| ||

March 4, 1845 – March 4, 1849

|

41

| ||

March 4, 1849 – July 9, 1850

|

60

| ||

July 9, 1850 – March 4, 1853

|

52

| ||

March 4, 1853 – March 4, 1857

|

46

| ||

n/a

|

n/a

| ||

March 4, 1861 – April 15, 1865

|

42

| ||

February 22, 1862 – May 10, 1865

| |||

April 15, 1865 – March 4, 1869

|

54

| ||

March 4, 1869 – March 4, 1877

|

43

| ||

March 4, 1877 – March 4, 1881

|

45

| ||

March 4, 1881 – September 19, 1881

|

48

| ||

January 12, 1880 (Aged 43)

|

n/a

| ||

June 2, 1886 – March 4, 1889

|

21

| ||

March 4, 1889 – October 25, 1892

|

56

| ||

June 2, 1886 – March 4, 1889

|

28

| ||

March 4, 1897 – September 14, 1901

|

49

| ||

September 14, 1901 – March 4, 1909

|

40

| ||

March 4, 1909 – March 4, 1913

|

47

| ||

March 4, 1913 – August 6, 1914

|

52

| ||

December 18, 1915 – March 4, 1921

|

43

| ||

March 4, 1921 – August 2, 1923

|

60

| ||

August 2, 1923 – March 4, 1929

|

44

| ||

March 4, 1929 – March 4, 1933

|

54

| ||

March 4, 1933 – April 12, 1945

|

48

| ||

April 12, 1945 – January 20, 1953

|

60

| ||

January 20, 1953 – January 20, 1961

|

56

| ||

January 20, 1961 – November 22, 1963

|

31

| ||

November 22, 1963 – January 20, 1969

|

50

| ||

January 20, 1969 – August 9, 1974

|

56

| ||

August 9, 1974 – January 20, 1977

|

56

| ||

January 20, 1977 – January 20, 1981

|

49

| ||

January 20, 1981 – January 20, 1989

|

59

| ||

January 20, 1989 – January 20, 1993

|

63

| ||

January 20, 1993 – January 20, 2001

|

45

| ||

January 20, 2001 – January 20, 2009

|

54

| ||

January 20, 2009 to date

|

45

|

Capitals of the United Colonies and States of America

Philadelphia

|

Sept. 5, 1774 to Oct. 24, 1774

| |

Philadelphia

|

May 10, 1775 to Dec. 12, 1776

| |

Baltimore

|

Dec. 20, 1776 to Feb. 27, 1777

| |

Philadelphia

|

March 4, 1777 to Sept. 18, 1777

| |

Lancaster

|

September 27, 1777

| |

York

|

Sept. 30, 1777 to June 27, 1778

| |

Philadelphia

|

July 2, 1778 to June 21, 1783

| |

Princeton

|

June 30, 1783 to Nov. 4, 1783

| |

Annapolis

|

Nov. 26, 1783 to Aug. 19, 1784

| |

Trenton

|

Nov. 1, 1784 to Dec. 24, 1784

| |

New York City

|

Jan. 11, 1785 to Nov. 13, 1788

| |

New York City

|

October 6, 1788 to March 3,1789

| |

New York City

|

March 3,1789 to August 12, 1790

| |

Philadelphia

|

Dec. 6,1790 to May 14, 1800

| |

Washington DC

|

November 17,1800 to Present

|

Book a primary source exhibit and a professional speaker for your next event by contacting Historic.us today. Our Clients include many Fortune 500 companies, associations, non-profits, colleges, universities, national conventions, PR and advertising agencies. As a leading national exhibitor of primary sources, many of our clients have benefited from our historic displays that are designed to entertain and educate your target audience. Contact us to learn how you can join our "roster" of satisfied clientele today!

Hosted by The New Orleans Jazz Museum and The Louisiana Historical Center

Hosted by The New Orleans Jazz Museum and The Louisiana Historical Center

Historic.us

A Non-profit Corporation

A Non-profit Corporation

Primary Source Exhibits

727-771-1776 | Exhibit Inquiries

202-239-1774 | Office

202-239-0037 | FAX

Dr. Naomi and Stanley Yavneh Klos, Principals

Naomi@Historic.us

Stan@Historic.us

Primary Source exhibits are available for display in your community. The costs range from $1,000 to $35,000 depending on length of time on loan and the rarity of artifacts chosen.

|

| U.S. Dollar Presidential Coin Mr. Klos vs Secretary Paulson - Click Here |

The United Colonies of North America Continental Congress Presidents (1774-1776)

The United States of America Continental Congress Presidents (1776-1781)

The United States of America in Congress Assembled Presidents (1781-1789)